SFTB 5.1: "The Idol of the Flies" by Jane Rice

Original artwork by William Kolliker for "The Idol of the Flies," Unknown, June 1942.

By Scott Nicolay

Welcome back, dear readers! Or perhaps I should ask you to welcome me back—I know it has been a while. I hope you will be forgiving and also recognize the debt of gratitude that we all owe to my partner in this project: artist, scholar, and activist Michael Bukowski. All this time that I have “been away,” his enthusiasm for Stories from the Borderland (catch up with previous installments at www.scottnicolay.com/blog) has neither wavered nor waned, and now that I have completed my doctorate, the torch of his enthusiasm has rekindled my own. Moreover, even before academic demands forced me to set this project aside, Michael and I had already outlined a fifth series of Weird tales with Weird creatures to share with you, and Michael has already drawn and shared them! How can I not rise to the occasion of providing the texts to accompany his stunning strange images? So it is that Stories from the Borderland returns for a fifth series, bringing you as fine a story as is to be found within the medium: “The Idol of the Flies,” by Jane Rice (as of this posting, the story is available to read here).

Additional thanks for this selection go to fellow author and investigative journalist Ian McDowell, who championed Rice and her exquisitely sinister writing to me back before the pandemic (he also shared his enthusiasm for another author with whose work we will finish this series, but let’s take things one installment at a time). If you have read Jane Rice’s work, especially “The Idol of the Flies” (and if you haven’t, please beware of spoilers ahead), you already know that Ian’s recommendation was arrow-meets-bullseye impeccable. His esthetics and critical acumen continue to hold my respect. Ian also shared with me “The smart, sophisticated pulp fiction of Jane Rice,” a very helpful and insightful article that he wrote in 2017 about this important but neglected author (which comes with the caveat that his editor rewrote the piece with a heavy and less-than-careful hand). Ian was also kind enough to review this blog post before it went online.

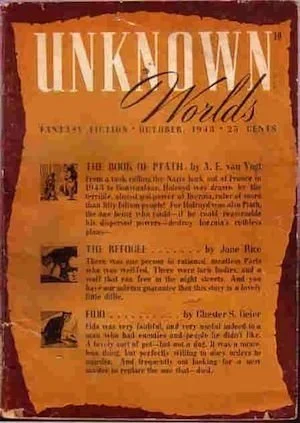

October 1943 issue of Unknown Worlds on which "The Refugee" by Jane Rice had cover billing.

One positive development we have witnessed since I had to place Stories from the Borderland on hiatus is the increasing attention devoted to the foundational women authors of Weird Fiction. As I write this, Michael Bukowski himself is preparing for a panel on Margaret St. Clair at the 2024 NecronomiCon Providence, and my partner and The Outer Dark co-producer Anya Martin—who does all the work of formatting and posting these essays online—is also scheduled to moderate a panel examining the work of the great surrealist author and painter Leonora Carrington. Both panels were recorded and will air this fall on The Outer Dark podcast on This Is Horror. Most of all, I hear the “Women of Weird Tales” mentioned with increasing frequency. Jane Rice, however, was not one of the Women of Weird Tales. She made her bones—and published “The Idol of the Flies”—in a distinctly different venue.

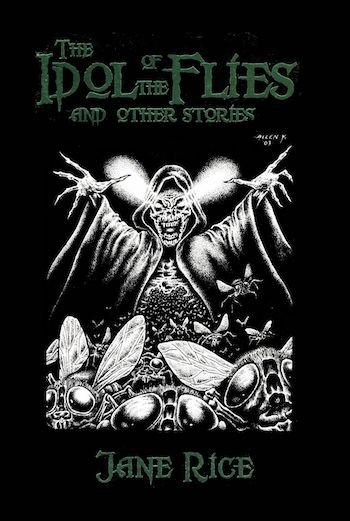

Jane Dixon Rice (1913–2003) began publishing fiction in 1940, in John W. Campbell’s Unknown (later Unknown Worlds) with “The Dream,” and she continued placing her stories there until wartime paper shortages shut the magazine down. Her second most popular story, “The Refugee,” appeared in the final issue in October 1943, with cover billing. According to Stefan R. Dziemianowicz, in his introductory essay to The Idol of the Flies and Other Stories (2003), Rice was the only author who was not also part of Campbell’s regular stable at Astounding to consistently receive this star treatment at Unknown Worlds. After Unknown Worlds folded, Rice disappeared from print for almost two decades. She reappeared several times, on each occasion after another lengthy hiatus, with a cluster of new stories. The aforementioned 2003 collection of her work, edited by Dziemianowicz and Jim Rockhill, and published by my late friend and mentor John Pelan under his Midnight House imprint, marks the only time her fiction has been gathered under one cover, and that limited edition has been out of print for over two decades now. Although two of her stories—“The Idol of the Flies” and “The Refugee”—were frequently anthologized during the latter half of the twentieth century, their popularity has dwindled in recent decades, with “Idol” only seeing two reprints in the last 30 years, and “Refugee” only one (other than their inclusion in the Midnight House collection, of course). Notably however, the one recent appearance of the latter story was in Library of America’s 2009 anthology American Fantastic Tales: Terror and the Uncanny from the 1940s to Now, edited by the late Peter Straub—a very respectable neighborhood. What this means, however, is that an entire generation of writers and readers is likely unfamiliar with her work. Perhaps this essay can address that somewhat.

1972 Paperback edition of William March's The Bad Seed.

Jane Rice’s work is remarkable above all for the quality of her prose: her attention to detail, her mastery of narrative in the short form, and the realism and nuance of her dialogue. All these qualities will strike the reader of “The Idol of the Flies” in the first page or two, but in this story, Rice also takes her narrative to an uncommon level. Rather than relying on a single plot device or trope, she presents the reader with several at once: the Bad Seed, demonic summoning, and The Weird—the latter arriving in the form of some deeply Weird creatures squirming and swimming about in their own obscure dimension. Most other writers would have been content to deploy only one of these elements, and would likely have split the others across multiple stories in the hopes of selling them separately. Jane Rice, however, does not hold back. I love it when an author takes these chances, practically throwing away elements that would have been the focus of an entire story in the hands of a lesser writer. I have seen this also in the work of Jean Ray, a.k.a. the Belgian Poe, whose fiction I have been translating for Wakefield Press. This approach, when accomplished successfully, is one mark of a writer at the height of their powers. Although Rice was not nearly so prolific as Ray, she also knew how to achieve this kind of richness in a story without losing control of its overall unity, and both authors achieved genuinely poetic qualities in their best work.

“The Idol of the Flies” originally saw print in the June 1942 issue of Unknown Worlds—a full 12 years before William March’s novel The Bad Seed, which was published in 1954, which has since been adapted for the stage, the cinema, and television (twice), and from which the name of the trope obviously derives. Thus, this trope was no cliché when Jane Rice employed it—it was not even yet established. This timing also places Rice’s story more than a decade ahead of one of the other most obvious foundational examples of the Bad Seed/evil child trope, “It’s a Good Life,” by Jerome Bixby, which was adapted for the original Twilight Zone TV series in 1961 (watch clip here), and again in the infamous Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), with various parodies and homages appearing in Calvin and Hobbes, The Simpsons, and elsewhere. The story originally appeared in Star Science Fiction Stories No.2 in 1953. Unlike March’s novel, the terrible little boys in both Rice’s story and Bixby’s wield significant supernatural powers.

Bill Mumy as Anthony Fremont" in "It's a Good Life" (The Twilight Zone, S3, Ep8), originally aired November 3, 1961.

Other early examples that fit the Bad Seed model with varying degrees of accuracy include:

Robert Bloch “Sweets to the Sweet” (1947)

Ray Bradbury “Let’s Play ‘Poison” (1946); “The Playground” (1952); “The Small Assassin” (1962);

Margaret St. Clair “Brenda” (1954)

John Wyndham The Midwich Cuckoos (1957) (novel)

William Trevor “Miss Smith” (1967)

R. Chetwynd-Hayes “The Cradle Demon” (1978)

Significantly, all of these postdate “The Idol of the Flies” by years, if not decades. One might point as far back as “Gabriel-Ernest” by Saki (H. H. Munro, 1870–1916), first published in 1909, but that tale is arguably more focused on lycanthropy, and the “child” in it is older than Rice’s, apparently at least an adolescent. One might even consider “The Ransom of Red Chief” by O. Henry (William Sydney Porter), first published in 1907 in the Saturday Evening Post, but that story lacks any of the supernatural elements or direct malevolence of Rice’s work and most other, later examples.

The Chronicles of Clovis (1911) was Saki's third short story collection, including the iconic "Sredni Vashtar."

By the 1970s, of course, the Bad Seed/evil child had become a major theme in American cinema, with prominent examples including Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), and The Omen (1976). Critics so often have pointed out how each generation’s movie monsters reflect its particular fears that this interpretation has become its own cliché. Prior to World War II, we have “strange foreigners and what are they up to?” After the war, the emphasis shifts to the effects of radioactivity. Thus, in the ’70s, horror films that sublimated the generation gap became box office gold; i.e. “these strange kids and what are they up to?” But “The Idol of the Flies” largely anticipates this theme, especially in regard to its almost-inevitable corollary: “it must be the work of the devil.”

None of this is intended to suggest that Jane Rice created the Bad Seed/evil child trope, and/or that her story influenced other, later, better-known examples. She did, however, offer one of its earliest, most focused, and distinctive examples. Moreover, her Pruitt is certainly a stellar example of the Bad Seed character, and a truly rotten kid by any standard. I am not suggesting however, that “The Idol of the Flies” appeared ex nihilo and had no obvious antecedents. In his 2017 article on Jane Rice, Ian McDowell points out the similarities between both of Rice’s most famous stories, and two even better-known tales by Saki, including the aforementioned “Gabriel-Ernest” (Rice’s “The Refugee”). In fact, the lycanthropes in these two works or so similar to each other that Rice’s story probably should be considered a sequel to Saki’s—an exceedingly clever sequel to be sure. We will return to these two stories and their possible relationship later.

John Collier's "Thus I Refute Beelzy" appeared in his debut collection, Presenting Moonshine (Viking Press, 1941).

McDowell also mentioned certain resemblances between “The Idol of the Flies” and another iconic Saki story, “Sredni Vashtar,” originally published in 1910. McDowell suggests that Rice’s tale represents an inversion of Saki’s. His idea has considerable merit. “Sredni Vashtar” contains many of the elements that Rice develops at greater length in her tale, with the main difference being that Conradin, the young boy in Saki’s tale, is far more sympathetic than Rice’s Pruitt, and he seeks supernatural vengeance only in self-defense. He is a victim, not a villain. In this example, we also potentially see the beginnings of Roald Dahl’s 1961 children’s novel James and the Giant Peach. In that story, young James Henry Trotter is also mistreated by awful guardians, Aunty Spiker and Aunty Sponge. James does not seek supernatural vengeance, but the opportunity to achieve it arrives unheralded and on its own.

Nor is “Sredni Vashtar” the only possible antecedent for “The Idol of the Flies.” Another very prominent and very likely candidate is John Collier’s “Thus I Refute Beelzy,” originally published less than two years before Rice’s story, in the October 1940 issue of The Atlantic, and reprinted the following year in Collier’s debut collection Presenting Moonshine (Viking Press, 1941). Both “Sredni Vashtar” and “Thus I Refute Beelzy” have been heavily anthologized since their first appearances, with reprints continuing solidly into the current decade. The two stories have even appeared several times between the same covers. Yet neither “Sredni Vashtar” nor “Thus I Refute Beelzy” inherently represents a Bad Seed story: the young boys in each story are not intrinsically evil; rather they are pushed to their respective breaking points by emotionally abusive guardians. Otherwise, however, “The Idol of the Flies” shares too many elements with both these tales to dismiss the question of possible inspiration out of hand—especially given the already probable connection between Saki’s “Gabriel-Ernest” and Rice’s “The Refugee.”

The Idol of the Flies and Other Stories (Midnight House, 2003).

In his introduction to The Idol of the Flies and Other Stories, Dziemianowicz suggests “that Rice was a careful observer of her colleagues’ work.” In this case, we should not assume that her attention to other writers ended with the efforts of her contemporaries. T. S. Eliot famously wrote, in his 1920 essay “Philip Massinger”: “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.” Although this line, in altered form, has been attributed to both Churchill and Wilde, it is indeed one of Eliot’s. Although I myself find Eliot a retrogressive force in modernism and am not a great admirer of his work, I am a fan of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and this particular zinger. It is, I feel, especially applicable to Jane Rice and her two most-celebrated stories.

Just as the final twist of “The Refugee” goes far beyond “Gabriel-Ernest,” achieving “something different,” perhaps even “something better,” Rice combines elements of both “Sredni Vashtar” and “Thus I Refute Beelzy” into something absent in either of its antecedents. Although the similarity between all three of these stories is almost unmistakable, the two young boys in Saki’s and Collier’s stories were more beleaguered than truly bad, whereas Rice’s Pruitt is himself a genuine monster, and the full extent of his evil, which initially appears to be limited to malicious pranks, is revealed near the end of the story. At that point it becomes clear how Rice might have written “The Idol of the Flies” as a sort of “slant” sequel to Collier’s tale, to repurpose a term from poetics, imagining how young Simon might have behaved in a new household after the events of his story. Rice appears to have combined Saki’s Conradin with Collier’s Simon and given her version the seemingly obvious twist of “what if the guardian is good, but the little boy is the monster?” The corollary that follows is that the boy should be the one who receives his just desserts at the end.

"Des larves si hideuses," by Odilon Redon, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Again, the possibility of such a relationship between the three tales is reinforced by the almost definite relationship between Saki’s “Gabriel-Ernest” and Rice’s “The Refugee.” The descriptions of the lycanthropic boys in the two stories are too close for coincidence, the main difference being that Rice’s werewolf seems a few years older than Saki’s, something that is necessary to achieve the story’s sexual tension. This age also serves the story’s wartime setting and plot, which along with the quality of Rice’s writing, place it in the territory of similar work by Irish-British novelist Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973). Perhaps Rice imagined “Gabriel-Ernest” as aging only very slowly, or perhaps she simply intended the boy in her story as a variant of the one in Saki’s, rather than the exact same one. Her tale, written and published during WWII, and set during the Nazi occupation of France, allows her to explore ideas that Saki could hardly have considered in 1910. She does so elegantly. If we accept the poetic quality of Rice’s prose, both “Idol” and “Refugee” provide perfect examples of Eliot’s dictum: she may have taken elements from her models, but she made them “into something better, or at least something different.”

As excellent as “The Idol of the Flies” is, I have not yet touched on the aspects of the story that place it in the category of Weird fiction. The Bad Seed trope does not inherently belong to The Weird, even less so does the summoning of demons. These elements generally belong to conventional horror. Rice adds a special piece, however, which becomes a plot point of its own and transforms this into a Weird Tale: Among his other eccentricities, Pruitt has the ability to enter a trance state, which he calls the “not-thinking-time.” During these periods, he is able to see strange creatures, reminiscent of some of the entities from H.P. Lovecraft’s 1934 story “From Beyond,” or certain works of Odilon Redon, such as “Des larves si hideuses” a print that accompanied his 1896 translation of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1859 story “The Haunted and the Haunters”: “queer, half-formed dream things that would float through his mind. Like dark polliwogs. Propelling themselves along with their tails, hinting at secrets that nobody knew . . .” Pruitt dreams of capturing one of these creatures, of acquiring its esoteric secrets, and this occult desire propels the story to its satisfying climax. With these hideous larvae in their mysterious and wholly other realm, Jane Rice propels “The Idol of the Flies” solidly into The Weird.

Recent Alma Edition of "Cruise of Shadows," by Jean Ray. The English language edition is available from Wakefield Press.

The combination of Judeo-Christian mythology and pure cosmic horror in this story is another remarkable element. Normally, the two modes do not mix well, and one certainly does not encounter this mix in the work of most writers of the Weird Tales circle. Once again, Jean Ray offers a comparison, however. A notable example is “Mondschein-Dampfer,” from his 1932 collection Cruise of Shadows. A favorite of mine from his oeuvre, this tale contains one of the best “deal-with-the devil” stories ever written, alongside references to Einstein’s theory of relativity, non-Euclidean geometry, and “the stars, those unknown worlds . . . millions of leagues from the dark orbit where you think you see them twinkling.” In Ray’s story, the strange, unknowable universe revealed by modern physics becomes a comfort and an escape for the protagonist after his encounter with Mephistopheles—a very different arrangement than one finds in the work of most Anglophone Weird writers, who find only horror in the strangeness of the cosmos.

Rice’s story is not like Ray’s in this regard (and it is almost impossible that she might have read it), but her particular method for combining cosmic horror and Beelzebub is just as atypical in Weird Fiction as Jean Ray’s juxtaposition of Mephistopheles and Einstein. In “The Idol of the Flies,” Pruitt’s fixation with the creatures of this mysterious and apparently extra-dimensional otherworld is what finally leads him to take a step too far and unintentionally summon the demonic entity with whom he has been trafficking all along—the same one that served as Simon’s invisible—but not so incorporeal—friend in “Thus I Refute Beelzy.” And unlike in Saki’s story, or Collier’s (or Dahl’s), Pruitt himself suffers a comeuppance, rather than his guardian, who in this case was not abusive, just oblivious.

Star Science Fiction Stories no. 2, which included "It's a Good Life," by Jerome Bixby.

Here then is where Rice takes the borrowed elements of her models and makes them into something different. As McDowell suggested, “The Idol of the Flies” offers an inversion of both “Sredni Vashtar” and “Thus I Refute Beelzy.” In her story, the boy is the bad one, not the guardian, and thus it is the boy who pays the price. And although I am not suggesting that Jerome Bixby drew on Rice’s story for “It’s a Good Life,” another lasting little masterpiece of The Weird, that is certainly also a possibility since Unknown magazine was iconic in the 1940s to readers who wants their speculative literature with a flavor of fantasy or horror. The twist that Bixby adds and asks us to consider is “what if there are no consequences for the boy, ever?” Whatever the influence of Rice, Bixby, and other early contributors to the Bad Seed trope, from this point onward the focus shifts to bad—often openly malevolent—children (usually boys, until March’s novel, although St. Clair’s “Brenda” from 1954, regarding which I have written in this series before, features a particularly horrible little girl, and is fully Weird: it even appeared in Weird Tales—and on Night Gallery). How much of this reflects an older generation’s initial experiences in parenting the baby boomers? Unlike Rice’s deeply strange “dream things,” fiction does not exist outside of time and historical context, and every author’s work is framed by historical context to at least some degree.

In order to view Michael Bukowski’s excellent and unsettling interpretation of one of Rice’s “Thinking-Time-Dream-Things,” please follow this link, and if you feel inclined, share both links with your friends on social media, as neither Michael nor I inhabit those realms any longer.

We can promise you that this initial entry in the fifth sequence of Stories from the Borderland is just the beginning, with at least four more weird creatures already drawn and four more essays already completed and waiting to accompany them. We have even the initial work on a sixth sequence with five more stories—and five more creatures—lurking in the shadows. In the meantime, thank you for rejoining us, and we hope you will return in two weeks for our next installment, which will offer two stories that portray weird cosmic horror on both the smallest scale and the largest—both of them by the same author.